Overview

Preliminaries

Before we get started, I have to say something about the importance of having good information. Just like using any calculation, garbage in gives garbage out. If you tell the efficiency calculator that you have 5.5 gallons, but you actually have 5.7 gallons, then all of the calculations have a substantial margin of error. To that end I’m going to annoyingly list a couple methods of accurately measuring your volumes, how to read a hydrometer, and a refractometer.{: .notice}

Useful Measurements on Brewday

To fully understand your system, and to figure out what went wrong, you need at least three sets of data. First runnings gravity and the strike volume gives grain absorption rate, and conversion efficiency. Pre-boil gravity and volume gives total mash efficiency, if you also have the first runnings info then you can calculate the lauter efficiency as well. Post boil gravity and volume gives the boil off rate and mash efficiency. Note that all volume measurements should have temperature measurements associated with them, see #Volumes for more info.

Predictability vs Consistency

I have been seeing some misleading posts lately regarding consistency in their efficiencies, and so I propose separating these two concepts. I realize this is a bit of semantics, but the difference is that the two concepts would be much easier for new and intermediate brewers to grasp instead of being worried when there brew isn’t hitting a listed OG at the “standard” of 70% mash efficiency. A consistent efficiency would then only apply to doing the same recipe repeatedly, while a predictable efficiency should be able to take your average efficiency and your process into account and using a simulator like my own to predict what a comparable efficiency would be for this new recipe. Stating that “I always get 76%” is very misleading for new brewers, and doesn’t tell them anything about your setup or process without providing significantly more information. While getting exactly the same efficiency is great for nailing down a particular recipe, it’s not that useful for those that don’t repeatedly do the same brew. Predictable would instead say “I usually get 76% on an average brew, so for this large grain bill I should instead expect 64%.” Predictability should be the goal for understanding your system.

Accurately measuring my strike volume out. This is 1.31 Gallons.

Volumes

There are three common methods of measuring your volumes; dip sticks, rulers, and kettle etching. Dip sticks are usually a wooden dowels with notches placed every so often to indicate a volume for that particular kettle. A dip stick for one kettle will not work for another kettle as the diameters of the kettle, and thus the height of one gallon of water will be different. My main issue with this is that the very act of notching the dowel introduces an unnecessary source of error, so I don’t usually suggest going this route. Next up is the dip stick 2.0, also known as the humble ruler. While these are not pre-marked with volume measurements, they’re going to be much more accurate and versatile. Simply measure the interior of the kettle and use a little bit of math, the formula for the volume of a cylinder, to determine the volume of water or wort. Lastly kettle etching, while an interesting and useful project, it suffers from the same drawbacks as the lowly dip stick, low instrumental precision and being specific to the kettle applied. If you do go this route, I would suggest doing it in smaller increments than the typical half gallon, as measurement error is half the smallest unit of measurement on the instrument. With that said, there’s one more thing to be aware of, and that’s thermal expansion ie. Liquids expand as they’re heated and contract when they’re cooled. This means that anytime you measure the volume, you should also measure the temperature and record both of these values, then calculate the volume when at room temperature using the formula below.*

T = Temperature in Fahrenheit.

V = Volume when measured at Temp T.

Volume_Chilled = V / ((-4.93313863E-14 * Temp^5) + ( 0.0000000000436276055 * Temp^4)+( - 0.000000015543896 * Temp^3) + ( 0.00000378669661 * Temp^2) - ( 0.000233129892 * Temp) + 1.00407725 )

Example: 7.25 @ 158F = 7.09 @ once chilledUnless you’re extremely comfortable in your brewing setup, and don’t care about these calculations, then don’t eyeball your volumes.

Specific Gravity

Without a specific gravity reading, this entire post would be pointless. There are currently two tools typically used to measure your specific gravity, the hydrometer, and the refractometer.

Hydrometers

We’ve all used a hydrometer before, but did you know that for some hydrometers you’re supposed to read the gravity from the TOP of the meniscus and not the bottom? Weird I know, but to determine how yours is calibrated, use distilled water at the calibration temp indicated at the bottom of the hydrometer and it should read 1.000. There are temperature adjustment calculations, but they’re not very precise and introduce yet another point of error, however if you at least cool to room temp, it should be less than the instrumental error of the hydrometer scale (0.005 for most wide range hydrometers). The exception being short range hydrometers such as fg hydrometers that have higher precision due to the smaller range of readings.

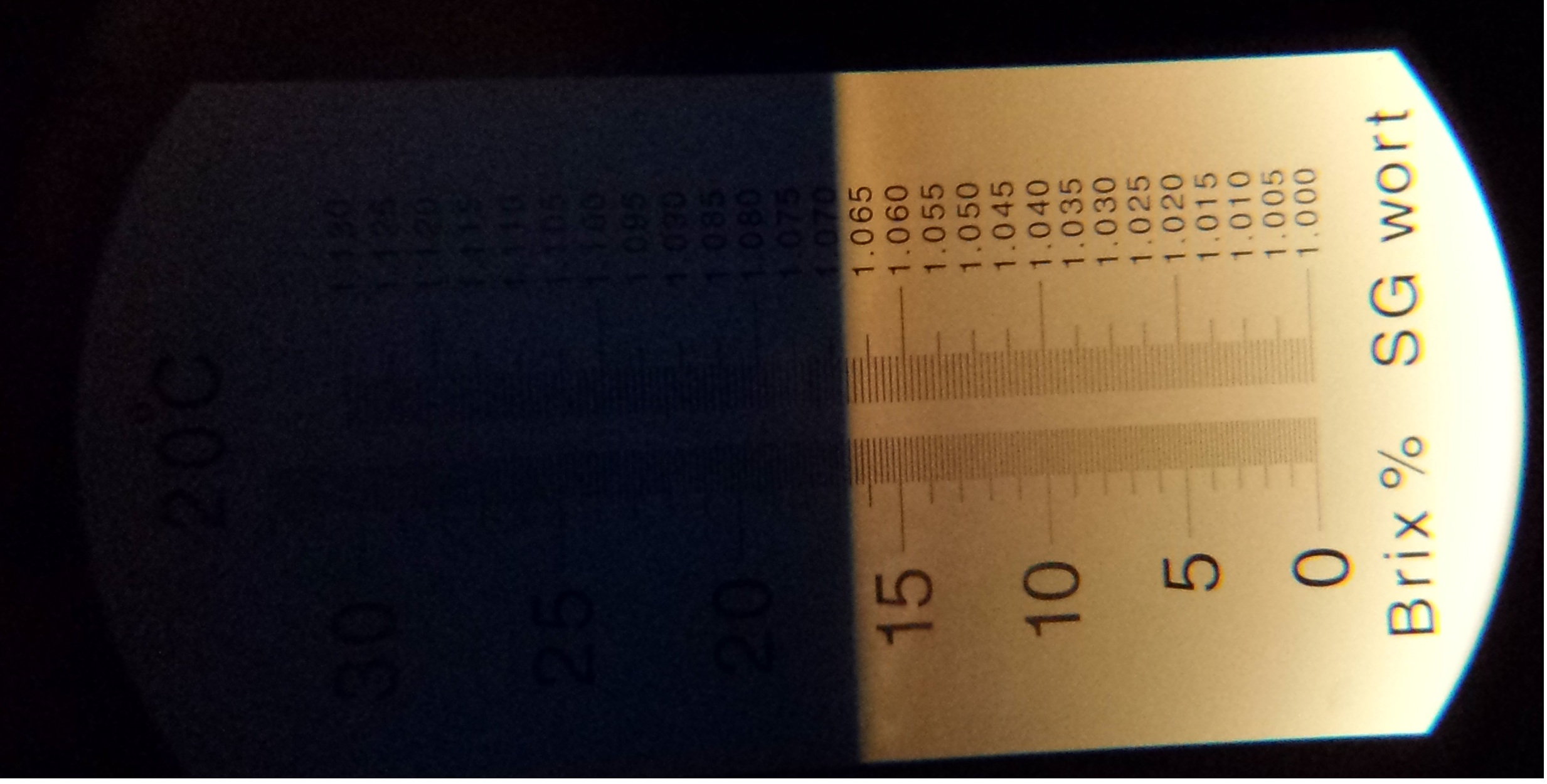

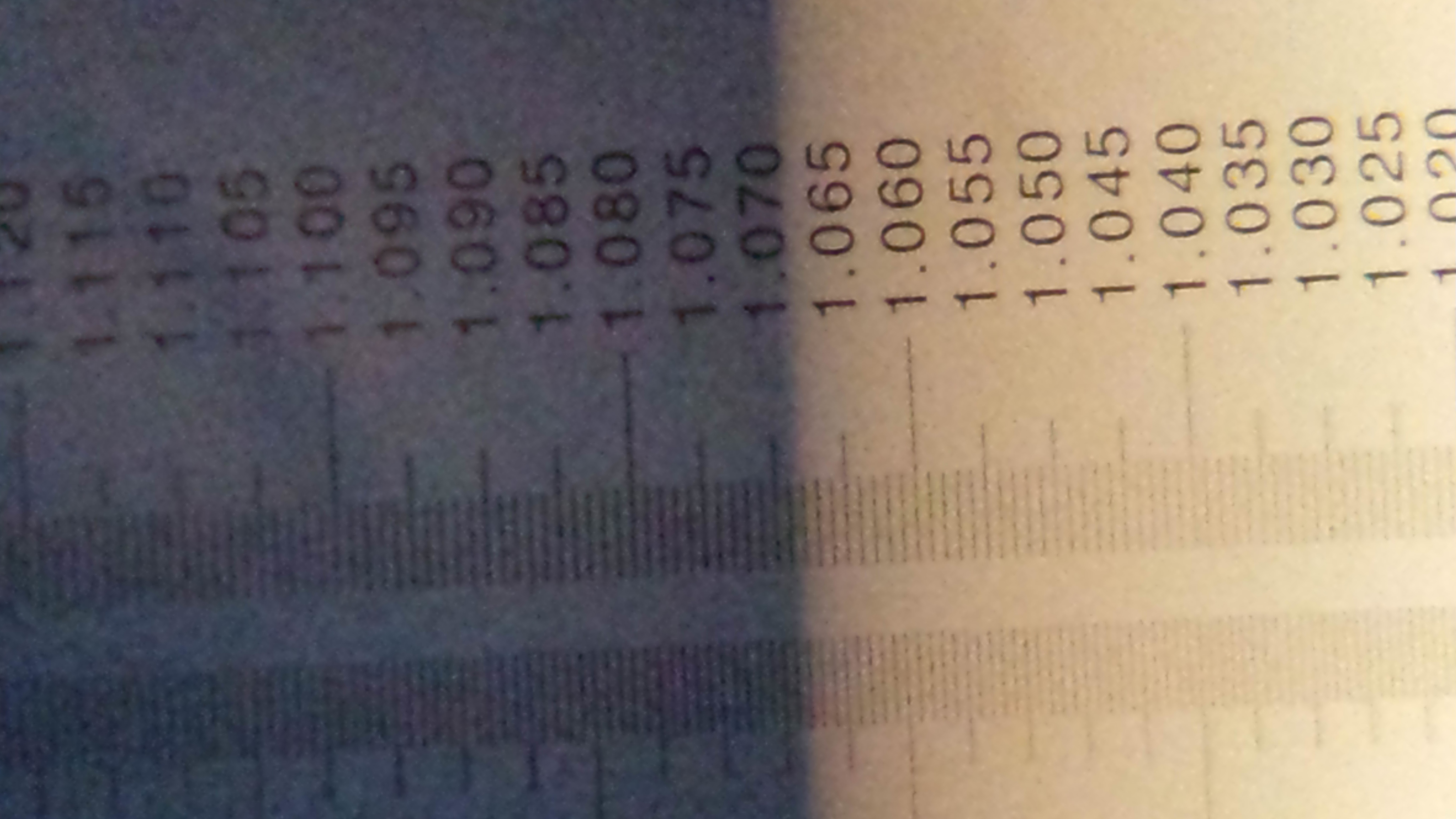

Refractometer

Using your refractometer may seem like a simple process, simply take a sample of wort/beer and look through the eye piece, but there’s a correction factor to account for. The wort correction factor is typically assumed to be 1.040 but will range with different worts and refractometers, some have attributed relationships between SRM and the wort correction factor. My hypothesis (I haven’t done enough data collecting yet to say for sure) is that it will instead depend on the sugar composition in the wort, and since dark beers are generally mashed at a higher temp, they have tend a greater number of long chain sugars and dextrins, so it may correlate better with mash temp or expected fg. The simple approach is to: 1) Calibrate your refractometer and hydrometer to zero using some water. 2) Make up some wort of known gravity using some water and DME. 3) Carefully measure the gravity using both instruments. 4) Divide the hydrometer reading by the refractometer reading, typical correction factors are 1.04 (sucrose based refractometer scales) or 1.00 (pre-calibrated in factory). Another thing to be aware of is the scale used during production of your hydrometer/refractometer, 25 brix should correspond to 1.106 and not 1.100. If it’s 1.100 then they used the old rule of thumb of multiplying by four, and so if this is the case you should always record the gravity reading in brix, and then convert to specific gravity using a tool of your choice. Lastly, you can use a refractometer to measure your final gravity but you have to use an accurate FG correction tool. The best ones at the moment are those based on the findings of Sean Terrill who published some great data on this subject.

Efficiencies

Alright, now that we got the boring parts over with, time to talk about the important things, calculating the effectiveness of your brewing process and system. Now don’t get me wrong, efficiency chasing is not the goal of this article, but rather understanding your system and being able to make a change in order to produce consistent beer. There are multiple kinds of efficiencies, conversion efficiency, lauter efficiency, mash efficiency, kettle efficiency, brew house efficiency, and each one is useful in determining something about your process. Professional brewers have additional types of efficiencies, like casting and packaging efficiency, which accounts for loss of volume due to evaporation during whirl pooling and hop stands. Each efficiency will be explained in the order at which it comes up in your brewday. All calculations were done using a batch sparge simulator created by user Doug293cz over at HBT, that was based on the findings and simulations of braukaiser then adapted for variable grain absorptions, which I then implemented into my calculator at Priceless’ BiabCal

Potential Extract

Before you can calculate any of your conversion efficiencies, you need to first know how to calculate your maximum potential extract. The potential extract is an upper bound on the amount of sugar that is able to be converted during the mash. In order to do that, you need to know the malt specifications, mainly the water content, and either the potential points per lb per gallon, or the fine grind extract (percentage). This varies for each batch of malt, as well as different malsters using the same type of grain, and unless you purchase the grain by the sack it’s unlikely you’ll be provided that information for this specific lot of malts. The best we can usually do is the databases of average malt specs, such as that at brewuniteds grain database, or within your recipe formulator of choice. Due to this variation in malt potential, there’s some margin of error in your potential extract and thus all of your efficiency calculations.

How to calculate

There’s two ways you can calculate the potential, the more accurate way is listed first.

Grain_Potential (PPG): Most grains have a potential of 36 points per gallon, but it can also range from 27 to 45.

Grain_Moisture (% of weight): Most grains have water content equal to 4% of their weight as water, but it can range from 3% to 9%.

Grain_Bill is the total weight of the grain bill added to the mash.

Dry_Weight = (1 - Grain_Moisture) * (Grain_Bill) = (1 - 0.04) * 12 = 11.52

Potential_Extract = Grain_Potential * Dry_Weight / Sugar_Density.

Potential_Extract = 36 * 12 / 46.173 = 9.35 Lb of extractSomewhat less accurate, but easier to calculate, is using total gravity points.

Grain_Potential (PPG): Most grains have a potential of 36 points per gallon, but it can also range from 27 to 45.

Total_Gravity_Points = Grain_Potential .

Total_Gravity_Points = 36 * 12 = 432 total points.Conversion Efficiency

This calculation compares the total amount of extract available from your grains, the potential extract, to the amount of sugar converted from the mash. The measurements needed are the volume and gravity of the first runnings of the mash. For those that aren’t familiar, the first runnings are the sweet liquor (unhopped/unboiled wort) that is drained off from the mash before you lauter or sparge. If you BIAB, this would be the wort released after pulling the grain bag and squeezing or allowing it to drain via suspension. There are techniques and mash parameters that affect conversion efficiency, however the most important technique is a proper dough in. It’s not enough to simply mix together the strike water and grains like you’re making pancakes or muffins. You want that stuff to be completely homogenous, ie no dough balls. STIR THE CRAP OUT OF IT. The mash parameters that affect conversion efficiency are the grain crush, mash times, mash temps, diastic power, mash thickness, and mash pH.

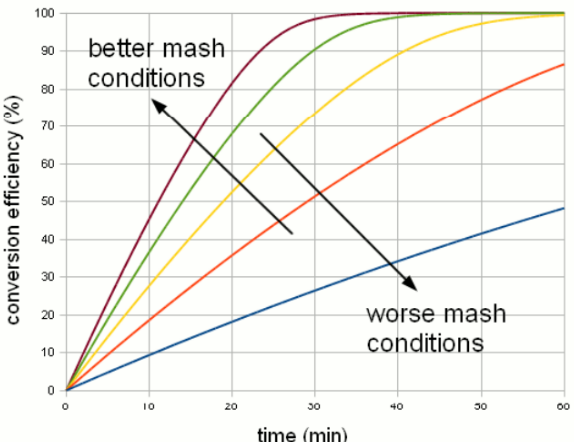

Conversion rate vs Mash conditions, from Kai Troeser NHC presentation

Conversion Rate

While none of these variables will necessarily lower the conversion efficiency, but they all affect the speed at which the conversion occurs. By increasing your conversion rate you can increase your conversion efficiency given the same time period, and you can’t always mash longer as there is a point at which mashing longer will produce zero difference as the enzymes denature. It’s my opinion that any mash that doesn’t reach full conversion by 50 minutes at the latest, probably has some issue with grain crush or dough in. I regularly get complete conversion within 40 minutes, occassionaly sliding into 45 minutes for bigger brews. Things that slow the conversion are: coarse grain crush, too high or too low of mash temps, low diastic power (low percentage of base malts in the recipe), thick mashes less than 1 qt/lb, thin mashes greater than 3.5 qt/lb and to a lesser extent poor mash ph. What I’ve read is that the mash ph will affect your flavor profile long before it significantly impacts the conversion efficiency. Do everything the opposite of the above to increase your conversion rate; mill finer, manage your mash ph, increase your diastic power or add enzymes, use a thinner mash in the 1.5-2.25 qt/lb range. Typical conversion efficiency is around 95%, with exceptional conversion rates being in the 97-98% range. Understand that each batch of malt will have slightly different grain specifics, and so your calculations are usually in the +-1% from that alone.

Relationship with Mash Thickness

There’s a lot of conflicting information regarding this subject, but two main principles at work. One is that higher concentrations of enzymes produces faster conversion rates and thus higher final conversion efficiency, with a typical recommended thickness of 1.25 qt/lb. This theory is particularly popular in older brewing texts. The other is that modern matls provide more than enough enzymes, and that the bottleneck is gelatinization of the malt granules, lowering the gravity of the mash which inhibits enzyme, and providing sufficient water to grain contact surface area. I’m of the latter mindset, and my experience is that finer grain milling providers a faster conversion as well as there is more surface area exposed which provides more contact for the enzymes and reduces the need for thorough gelatinization as the distance from the outside edge to the center of the milled grain is reduced. My current recommendation is to stay at or above 1.75 qt/lb in order to maximize conversion efficiency, with the caveat that there is little difference in the 1.5-2.5 qt/lb range. Try to avoid going lower than 1.25 qt/lb, or higher than 3.5 qt/lb. The last point is rarely an issue, as very few brewers mash that thin, even amongst biab.

Typical expected values

Typical conversion efficiency is usually in the 90-95% range, but it will depend on a wide variety of factors that I’ve already talked above. I wouldn’t start worrying about it unless you go below ~88% or so. If you do, or are otherwise concerned with your conversion efficiency, see the section on troubleshooting. Conversion rarely exceeds 96%, and if it does it usually is at least partially due to inaccurate grain parameters like the potential yield or the water content.

Calculating

Conversion efficiency is simple to calculate from measured data, and requires strike volume, first running gravity, and temp. As noted above, temp needs to be taken to calculate the room temp volume. Be sure to take a gravity reading while the sample is at the calibrated temperature as previously mentioned.

Calculating using extract method, you’ll need to convert the gravity reading into plato to use this approach.

Volume_Strike being the room temperature strike volume added to the mash.

Grain_Moisture (% of weight): Most grains have water content equal to 4% of their weight as water, but it can range from 3% to 9%.

Grain_Bill is the total weight of the grain bill added to the mash.

Measured_First_Running_Plato is the gravity reading, in Plato, of the first runnings sweet liquor.

Converted_Extract = -((Volume_Strike * 8.335 + (GBill * Grain_Moisture)) * Measured_First_Running_Plato) / (-100 + Measured_First_Running_Plato)

Conversion Efficiency = Converted_Extract / Potential_ExtractCalculating using gravity points method.

Volume_Strike being the room temperature strike volume added to the mash.

Grain_Bill is the total weight of the grain bill added to the mash.

Measured_First_Running_Plato is the gravity reading, in Plato, of the first runnings sweet liquor.

Converted_Extract = ( Measured_First_Running_Plato * Volume_Strike ) / Potential_Total_Gravity_PointsTroubleshooting

Check the crush, then check the crush again, then look at your mash Ph, check the crush, then look at your water chemistry, and check the crush again. If you still have low conversion efficiency it could mean your grains have a different yield than what is in the computers grain database, you might have issues with your strike temp and accidentally denatured some enzymes by doughing in too hot, you might need to crush finer, try a thinner mash, or mash longer. If you have a refractometer, take a gravity sample every 5 minutes, when the gravity has stopped increasing, mash another 10 minutes, if it’s still the same then your mash is done and no further conversion is going to take place. By taking gravity readings throughout the mash, you’ll determine when your mash completes total conversion which is useful for two reasons. First you can save yourself some time on brew day, and second you can determine the “quality” of your mash conditions. My mashes are typically completed by 45 minutes, where larger grain bills or smaller percentages of base malt take slightly longer. Graphing your conversion rate vs time, as shown above from braukaiser, or in my ‘equal runnings biab’ thread at homebrewtalk6 is a useful technique as well as it will give you further insight into the quality of your mash conditions.

Lauter Efficiency

The next step in the brewday after draining your mash tun is the sparge, or maybe you’re doing no sparge aka full volume mashing? Either way, you still have a lauter efficiency! This is a measure of how effective your sparge is, depending on your technique and equipment it’s usually 70-80%. The required measurements are volume and gravity of preboil. Losses in mash tun, or high absorption rates will kill this and bring this efficiency down very quickly. A proper batch sparge is usually performed exactly the same as the initial dough in, take your grains, combine it with some water, and stir the crap out of it. I recommend stirring with a whisk if possible as this batch sparge can sometimes be very thick. Let it rest for a few minutes, then stir the crap out of it again, then drain the second runnings. No sparge mash tun brews usually are around 69%, the same setup for BIAB is usually around 72% given the lower grain absorption rate. A batch sparge with a mash thickness around 1.5-1.75 qt/lb and near equal runnings should give about 80-81%* lauter efficiency. The same setup with a BIAB squeeze should increase that to about 86-87%* lauter efficiency. A fly sparge should at the very least increase your lauter efficiency by at least 3%, if you’re not at least matching the above batch sparge lauter efficiencies by fly sparging, you’re mash tun is probably not set up optimally for a proper fly sparge and you’re getting a considerable amount of channeling, my recommendation would be to do a proper batch sparge and see if you get better results. Even if you come out even, you’re saving a bunch of time.

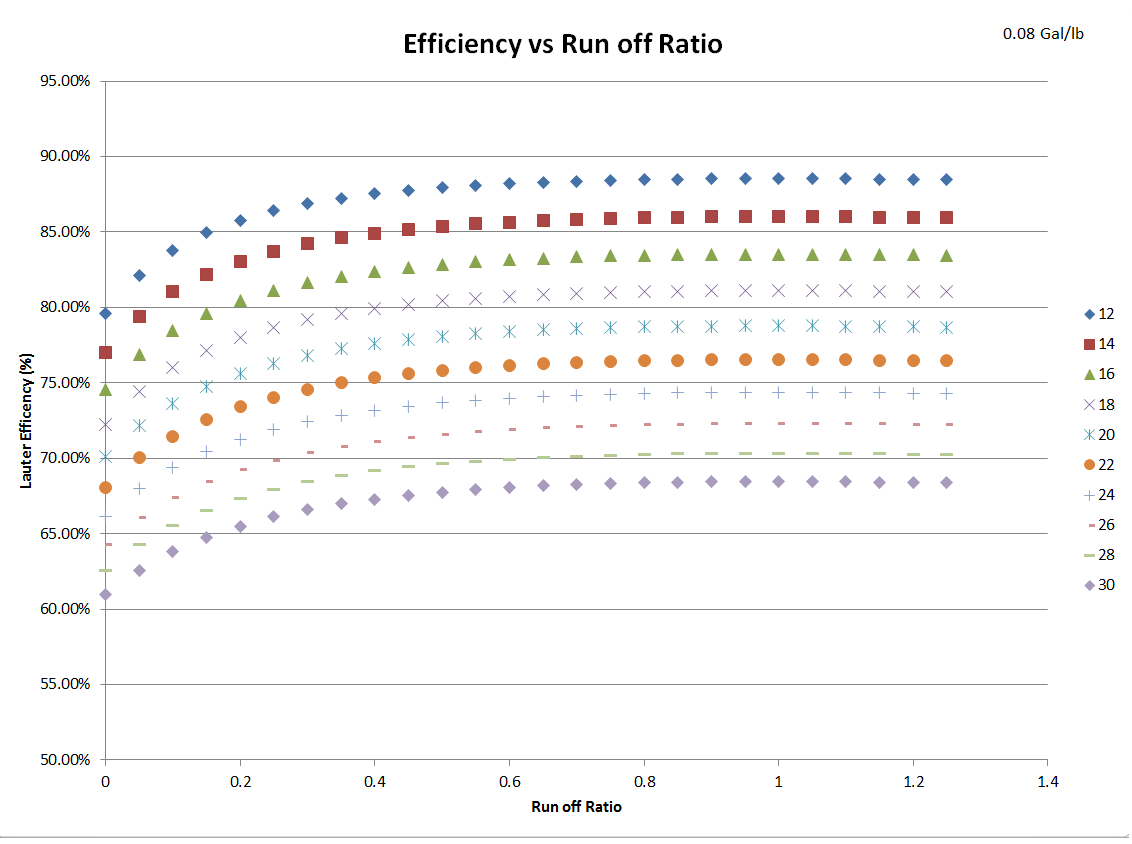

Typical Lauter efficiency curve for BIAB for various run off ratios. Zero run off ratio being no-sparge/Full volume mash

Calculating

The calculation for this is very simple, divide the recovered extract by the total potential extract and you get your lauter efficiency. Note that the majority of this lauter efficiency comes from your first runnings, and the remaining portion is attributed to the effectiveness of your sparge.

Volume_Strike being the room temperature strike volume added to the mash.

Grain_Moisture (% of weight): Most grains have water content equal to 4% of their weight as water, but it can range from 3% to 9%.

Grain_Bill is the total weight of the grain bill added to the mash.

Measured_First_Running_Plato is the gravity reading, in Plato, of the first runnings sweet liquor.

Converted_Extract = -((Volume_Strike * 8.335 + (GBill * Grain_Moisture)) * Measured_First_Running_Plato) / (-100 + Measured_First_Running_Plato)

Lauter efficiency = Recovered_Extract / Total_Potential_ExtractTroubleshooting and typical expected values

Troubleshooting: A batch sparge with a mash thickness around 1.5-1.75 qt/lb and near equal runnings should easily be capable of 80-81%* lauter efficiency for 1.055 typical brew. The same setup with a BIAB squeeze should increase that to about 86-87%* lauter efficiency. A fly sparge should at the very least increase your lauter efficiency by at least 3%*, yielding ~84% or 90% lauter efficiency respectively. if you’re not at least matching the above batch sparge lauter efficiencies by fly sparging, you’re mash tun is probably not set up optimally for a proper fly sparge and you’re getting a considerable amount of channeling, my recommendation would be to do a proper batch sparge and see if you get better results. At the very least, you’ll save a substantial amount of time.

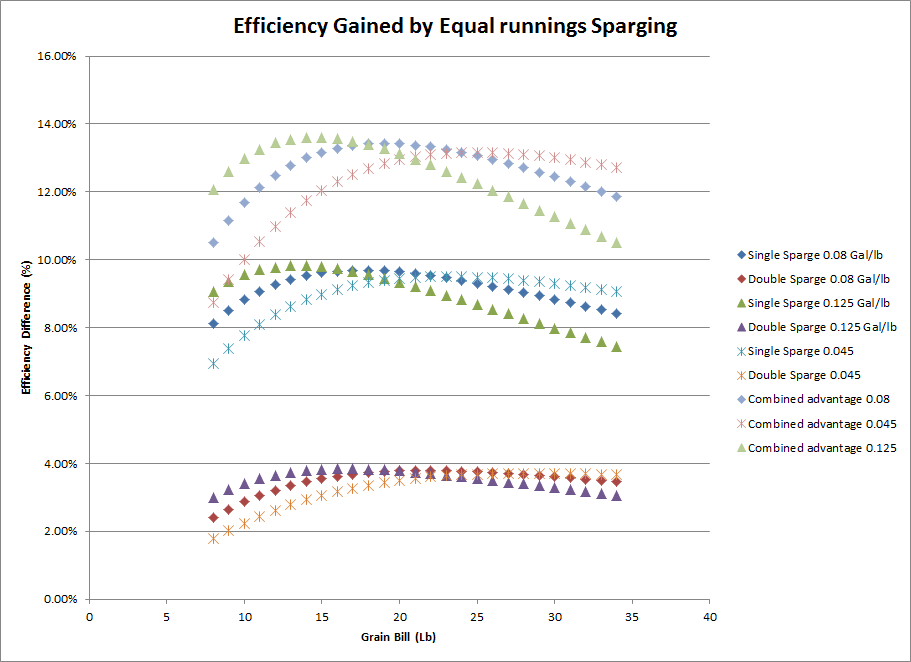

Efficiency gained from batch sparging for various typical scenarios

Mash Efficiency

Mash efficiency, is the combination of conversion and lauter efficiencies. However it’s of little use to anyone trying to troubleshoot or understand their setup despite being the second most commonly mentioned variable and I won’t go on much about it. That’s not to say that it’s a useless characteristic, as it’s extremely useful in formulating recipes.

Calculating Mash Efficiency

Mash = Lauter * ConversionTypical expected values

A batch sparge with a mash thickness around 1.5-1.75 qt/lb and near equal runnings should easily be capable of ~75%* mash efficiency for 1.055 typical brew. The same setup with a BIAB squeeze should increase that to about 79-80%* mash efficiency. A fly sparge should at the very least increase your mash efficiency by at least 3%*, yielding ~78% or 83% mash efficiency respectively. if you’re not at least matching the above batch sparge lauter efficiencies by fly sparging, you’re mash tun is probably not set up optimally for a proper fly sparge and you’re getting a considerable amount of channeling, my recommendation would be to do a proper batch sparge and see if you get better results. At the very least, you’ll save a substantial amount of time.

Brewhouse Efficiency

Similar to Mash efficiency, there’s not much going on here. Any losses after the boil occurs will affect this number. For those with zero apparent* kettle losses, brew house efficiency = mash efficiency. While this is usually the reference point when people say “I get xx efficiency”, this is a pretty useless metric in my experience as unless you have significant losses after chilling, it’s not going to help much for understanding your setup or troubleshooting an issue with lower/higher than expected gravity. I say apparent above because for some people they account for the hot break that coagulates during the boil at this point, while others transfer all of the wort including the proteins into the fermenter and let it settle out after fermentation with the goal being that an extended rest, and cold crash, will compact the proteins further. However this approach will give you a slightly higher apparent brewhouse efficiency than is actually true, as you’re counting the volume occupied by the proteins as wort volume. Traditionally, this is the number that is reporting in most recipes, however I believe that mash efficiency is the more generalized measure of your brewing process, as it is tied to the gravity and volume of the preboil wort, while the kettle loss is tied to the brewhouse efficiency and so if you have a different kettle loss, you will need to adjust your grain weights while if it was listed with the mash efficiency, this would be unnecessary to achieve the same wort gravity.

Calculating brewhouse Efficiency

T = Temperature in Fahrenheit.

V = Volume when measured.

Volume_Chilled = V * ( 1.05606 x 10^-15 x Temp - 7.43014 x 10^-13 x A25 + 2.19998 x 10^-10 x A24 - 3.74236 x 10^-8 x A23 + 5.Myths, Mashout, and More

The first myth on the agenda is that BIAB gets low mash efficiency. This is just not true. I have never met any brewer that does biab regularly, and has consistently gotten less than 70% mash efficiency. The fact of the matter is that by squeezing the grain bag, they’re increasing their lauter efficiency. All other things held equal, there is no way that this can decrease any other efficiency measurement. Lower absorption rate = higher lauter efficiency.

The second myth is related slightly, thin mashes do not give lower/slower conversion rates. Likewise, enzyme concentration has not been a convincing model in my experiments that can predict conversion rates, otherwise we would all be doing super thick mashes. You need sufficient enzyme concentrations, don’t go over ~3.5 qt/lb mash thickness, and you need good water to grain surface area exposure. This can be done by an inline hydration like in professional breweries, by recirculation, mashing thinner or by a thinner mash. I recommend 1.75-2.25 qt/lb if possible for good conversion efficiency without sacrificing too much lauter efficiency due to the decreased sparge volume and runnings ratio.

Mashouts

This might upset some people but a mashouts a purpose is NOT to increase efficiency, nor is it to significantly change the viscosity and make rinsing the sugars more effective… A mashout denatures the enzymes and locks in the wort composition. This really only applies in my mind for fly sparging, or other slow sparging methods. If you’re doing biab, or doing a 5-15 minute batch sparge then there’s no need to mash out at all. If you’re reporting a significant efficiency gain from a mashout then the most likely explanation is either due to a second sparge volume increasing your lauter efficiency or that you’re really extending your mash time and not getting full conversion in the original mash time and you’ll benefit as much or more by mashing longer, or crushing finer. However there is a special case here, where a higher temperature increases the activity of alpha enzymes which may further convert starches into complex chains of sugar. These long sugar molecules and dextrins are likely to give a higher fg however, and so I reiterate that you’re better off improving the characteristics of your mash to ensure a quick conversion rate.

A plea for clarity:”I always get ##% efficiency”

Lastly, I think it would be wonderful if everyone could stop saying I get xx efficiency, without saying which efficiency you’re talking about, when discussing their issues with new brewers. As that’s so arbitrary it’s all but useless. Instead discuss your conversion efficiency, lauter efficiency and your process so that they understand that there are more than one type and can actually try to figure out what went awry!

References and further reading

“BrewUnited’s Grain Database.” BrewUnited’s Grain Database. Web. https://www.brewunited.com/grain_database.php.

Doug293cz UserProfile - Homebrewtalk. Web. http://www.homebrewtalk.com/members/doug293cz/.

“Equal Runnings BIAB - Home Brew Forums.” Equal Runnings BIAB - Home Brew Forums. Web. http://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=548329.

“How to Add Permanent Volume Markings to a Kettle.” R/Homebrewing. Web. https://www.reddit.com/comments/1zeig4.

“How to Determine Your Refractometer’s Wort Correction Factor - Brewer’s Friend.” Brewers Friend. Web. http://www.brewersfriend.com/how-to-determine-your-refractometers-wort-correction-factor/.

John J. Palmer, How to Brew, Brewers Publications, Boulder CO, 2006

“Mash Efficiency. Brewhouse Efficiency. A Simple Explanation. - Home Brew Forums.” Mash Efficiency. Brewhouse Efficiency. A Simple Explanation. - Home Brew Forums. Web. http://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=540642.

“Refractometer FG Results.” SeanTerrill.com. Web. http://seanterrill.com/2011/04/07/refractometer-fg-results/.

Terril, Sean. “Refractometer Calculator.” SeanTerrill.com. Web. http://seanterrill.com/2012/01/06/refractometer-calculator/.

Terril, Sean. “Refractometer Calculator.” SeanTerrill.com. Web. http://seanterrill.com/2012/01/06/refractometer-calculator/.

Troeser, Kai. “First Wort Gravity and Mash Efficiency - Home Brew Forums.” First Wort Gravity and Mash Efficiency - Home Brew Forums. Web. http://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=68555.

Troeser, Kai. NHC 2010 presentation about efficiency and how to keep it predictable, 2010

Troeser, Kai. “The Science of Mashing” - German Brewing and More. Web. http://braukaiser.com/wiki/index.php?title=The_Science_of_Mashing.

Troeser, Kai. “Understanding Efficiency.” - German Brewing and More. Web. http://www.braukaiser.com/wiki/index.php?title=Understanding_Efficiency.